THE HISTORY OF

THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

Copyright, 1904, by Ames

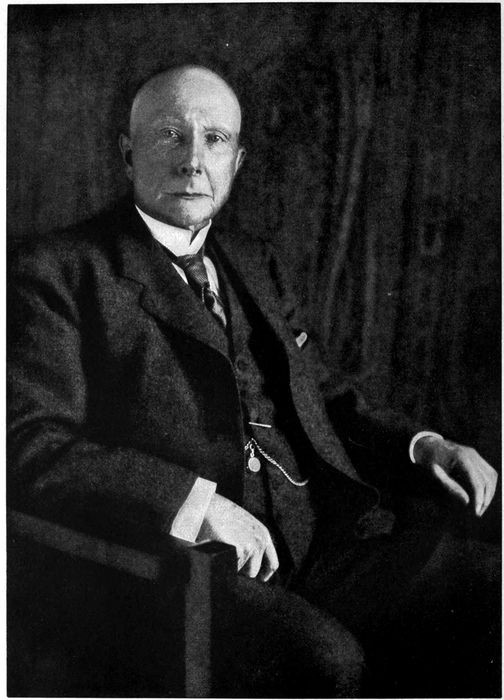

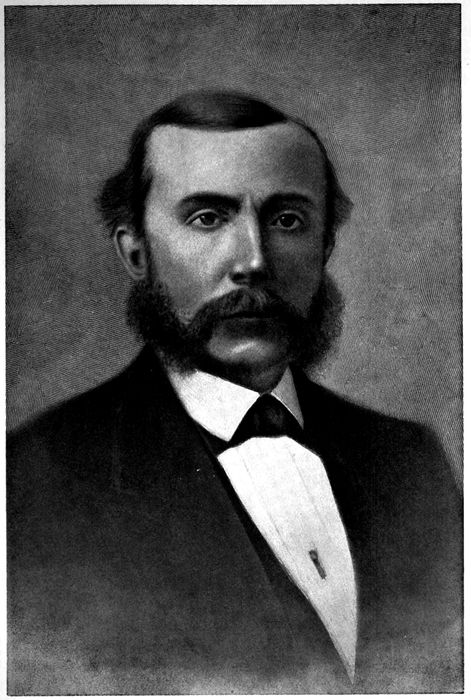

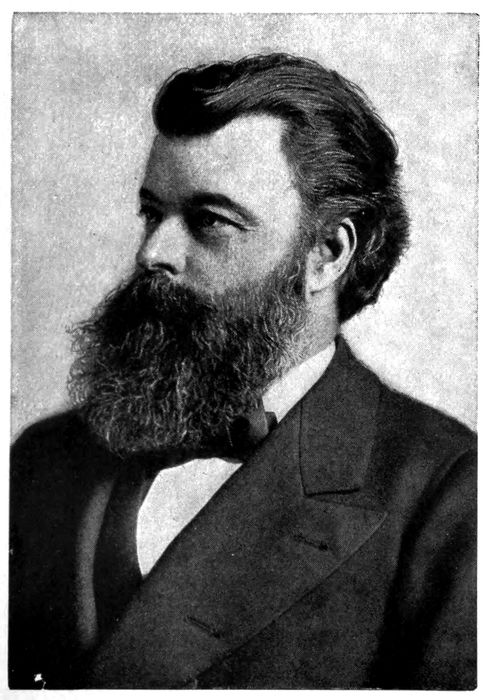

JOHN DAVISON ROCKEFELLER IN 1904

Born July 8, 1839

JOHN DAVISON ROCKEFELLER IN 1904

Born July 8, 1839

THE HISTORY OF

THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

BY

IDA M. TARBELL

AUTHOR OF THE LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN, THE LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE, AND MADAME ROLAND: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY

ILLUSTRATED WITH PORTRAITS, PICTURES AND DIAGRAMS

VOLUME ONE

NEW YORK

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

MCMV

Copyright, 1904, by

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

Published, November, 1904

Second Impression

Copyright, 1902, 1903, 1904, by The S. S. McClure Co.

“An Institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.”

EMERSON, IN ESSAY ON “SELF-RELIANCE.”

“The American Beauty Rose can be produced in its splendor and fragrance only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it.”

J. D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., IN AN ADDRESS ON TRUSTS,

TO THE STUDENTS OF BROWN UNIVERSITY.

vii

PREFACE

This work is the outgrowth of an effort on the part of the editors of McClure’s Magazine to deal concretely in their pages with the trust question. In order that their readers might have a clear and succinct notion of the processes by which a particular industry passes from the control of the many to that of the few, they decided a few years ago to publish a detailed narrative of the history of the growth of a particular trust. The Standard Oil Trust was chosen for obvious reasons. It was the first in the field, and it has furnished the methods, the charter, and the traditions for its followers. It is the most perfectly developed trust in existence; that is, it satisfies most nearly the trust ideal of entire control of the commodity in which it deals. Its vast profits have led its officers into various allied interests, such as railroads, shipping, gas, copper, iron, steel, as well as into banks and trust companies, and to the acquiring and solidifying of these interests it has applied the methods used in building up the Oil Trust. It has led in the struggle against legislation directed against combinations. Its power in state and Federal government, in the press, in the college, in the pulpit, is generally recognised. The perfection of the organisation of the Standard, the ability and daring with which it has carried out its projects, make it the pre-eminent trust of the world—the one whose story is best fitted to illuminate the subject of combinations of capital.

Another important consideration with the editors in deciding that the Standard Oil Trust was the best adapted to illustrate viiitheir meaning, was the fact that it is one of the very few business organisations of the country whose growth could be traced in trustworthy documents. There is in existence just such documentary material for a history of the Standard Oil Company as there is for a history of the Civil War or the French Revolution, or any other national episode which has divided men’s minds. This has come about largely from the fact that almost constantly since its organisation in 1870 the Standard Oil Company has been under investigation by the Congress of the United States and by the Legislatures of various states in which it has operated, on the suspicion that it was receiving rebates from the railroads and was practising methods in restraint of free trade. In 1872 and again in 1876 it was before Congressional committees, in 1879 it was before examiners of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and before committees appointed by the Legislatures of New York and of Ohio for investigating railroads. Its operations figured constantly in the debate which led up to the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887, and again and again since that time the Commission has been called upon to examine directly or indirectly into its relation with the railroads.

In 1888, in the Investigation of Trusts conducted by Congress and by the state of New York, the Standard Oil Company was the chief subject for examination. In the state of Ohio, between 1882 and 1892, a constant warfare was waged against the Standard in the courts and Legislature, resulting in several volumes of testimony. The Legislatures of many other states concerned themselves with it. This hostile legislation compelled the trust to separate into its component parts in 1892, but investigation did not cease; indeed, in the last great industrial inquiry, conducted by the Commission appointed by President McKinley, the Standard Oil Company was constantly under discussion, and hundreds of pages of ixtestimony on it appear in the nineteen volumes of reports which the Commission has submitted.

This mass of testimony, all of it submitted under oath it should be remembered, contains the different charters and agreements under which the Standard Oil Trust has operated, many contracts and agreements with railroads, with refineries, with pipe-lines, and it contains the experiences in business from 1872 up to 1900 of multitudes of individuals. These experiences have exactly the quality of the personal reminiscences of actors in great events, with the additional value that they were given on the witness stand, and it is fair, therefore, to suppose that they are more cautious and exact in statements than many writers of memoirs are. These investigations, covering as they do all of the important steps in the development of the trust, include full accounts of the point of view of its officers in regard to that development, as well as their explanations of many of the operations over which controversy has arisen. Hundreds of pages of sworn testimony are found in these volumes from John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Henry M. Flagler, H. H. Rogers, John D. Archbold, Daniel O’Day and other members of the concern.

Aside from the great mass of sworn testimony accessible to the student there is a large pamphlet literature dealing with different phases of the subject, and there are files of the numerous daily newspapers and monthly reviews, supported by the Oil Regions, in the columns of which are to be found not only statistics but full reports of all controversies between oil men. No complete collection of this voluminous printed material has ever been made, but several small collections exist, and in one or another of these I have been able to find practically all of the important documents relating to the subject. Mrs. Roger Sherman of Titusville, Pennsylvania, owns the largest of these collections, and in it are to be found copies of the rarest pamphlets. Lewis Emery, Jr., of xBradford, the late E. G. Patterson of Titusville, the late Henry D. Lloyd, author of “Wealth vs. Commonwealth,” William Hasson of Oil City, and P. C. Boyle, the editor of the Oil City Derrick, have collections of value, and they have all been most generous in giving me access to their books.

But the documentary sources of this work are by no means all printed. The Standard Oil Trust and its constituent companies have figured in many civil suits, the testimony of which is still in manuscript in the files of the courts where the suits were tried. These manuscripts have been examined on the ground, and in numerous instances full copies of affidavits and of important testimony have been made for permanent reference and study. I have also had access to many files of private correspondence and papers, the most important being that of the officers and counsel of the Petroleum Producers’ Union from 1878 to 1880, that covering the organisation from 1887 to 1895 of the various independent companies which resulted in the Pure Oil Company, and that containing the material prepared by Roger Sherman for the suit brought in 1897 by the United States Pipe Line against certain of the Standard companies under the Sherman anti-trust law.

As many of the persons who have been active in the development of the oil industry are still living, their help has been freely sought. Scores of persons in each of the great oil centres have been interviewed, and the comprehension and interpretation of the documents on which the work is based have been materially aided by the explanations which the actors in the events under consideration were able to give.

When the work was first announced in the fall of 1901, the Standard Oil Company, or perhaps I should say officers of the company, courteously offered to give me all the assistance in their power, an offer of which I have freely taken advantage. In accepting assistance from Standard men as from independents I distinctly stated that I wanted facts, and that I xireserved the right to use them according to my own judgment of their meaning, that my object was to learn more perfectly what was actually done—not to learn what my informants thought of what had been done. It is perhaps not too much to say that there is not a single important episode in the history of the Standard Oil Company, so far as I know it, or a notable step in its growth, which I have not discussed more or less fully with officers of the company.

It is needless to add that the conclusions expressed in this work are my own.

I. M. T.

I. M. T.

xiii

CONTENTS

Owner of the “Tarr Farm,” one of the richest oil territories on Oil Creek.

PREFACE

Pages vii–xi

CHAPTER ONE

THE BIRTH OF AN INDUSTRY

PETROLEUM FIRST A CURIOSITY AND THEN A MEDICINE—DISCOVERY OF ITS REAL VALUE—THE STORY OF HOW IT CAME TO BE PRODUCED IN LARGE QUANTITIES—GREAT FLOW OF OIL—SWARM OF PROBLEMS TO SOLVE—STORAGE AND TRANSPORTATION—REFINING AND MARKETING—RAPID EXTENSION OF THE FIELD OF OPERATION—WORKERS IN GREAT NUMBERS WITH PLENTY OF CAPITAL—COSTLY BLUNDERS FREQUENTLY MADE—BUT EVERY DIFFICULTY BEING MET AND OVERCOME—THE NORMAL UNFOLDING OF A NEW AND WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITY FOR INDIVIDUAL ENDEAVOUR.

Pages 1003–1037

CHAPTER TWO

THE RISE OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

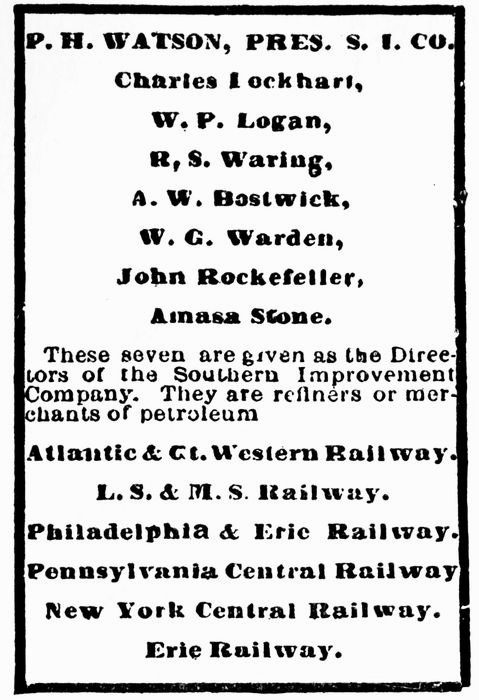

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER’S FIRST CONNECTION WITH THE OIL BUSINESS—STORIES OF HIS EARLY LIFE IN CLEVELAND—HIS FIRST PARTNERS—ORGANISATION OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY IN JUNE, 1870—ROCKEFELLER’S ABLE ASSOCIATES—FIRST EVIDENCE OF RAILWAY DISCRIMINATIONS IN THE OIL BUSINESS—REBATES FOUND TO BE GENERALLY GIVEN TO LARGE SHIPPERS—FIRST PLAN FOR A SECRET COMBINATION—THE SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY—SECRET CONTRACTS MADE WITH THE RAILROADS PROVIDING REBATES AND DRAWBACKS—ROCKEFELLER AND ASSOCIATES FORCE CLEVELAND REFINERS TO JOIN THE NEW COMBINATION OR SELL—RUMOUR OF THE PLAN REACHES THE OIL REGIONS.

Pages 1038–1069

xiv

CHAPTER THREE

THE OIL WAR OF 1872

RISING IN THE OIL REGIONS AGAINST THE SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY—PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ UNION ORGANISED—OIL BLOCKADE AGAINST MEMBERS OF SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY AND AGAINST RAILROADS IMPLICATED—CONGRESSIONAL INVESTIGATION OF 1872 AND THE DOCUMENTS IT REVEALED—PUBLIC DISCUSSION AND GENERAL CONDEMNATION OF THE SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY—RAILROAD OFFICIALS CONFER WITH COMMITTEE FROM PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ UNION—WATSON AND ROCKEFELLER REFUSED ADMITTANCE TO CONFERENCE—RAILROADS REVOKE CONTRACTS WITH SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY AND MAKE CONTRACT WITH PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ UNION—BLOCKADE AGAINST SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY LIFTED—OIL WAR OFFICIALLY ENDED—ROCKEFELLER CONTINUES TO GET REBATES—HIS GREAT PLAN STILL A LIVING PURPOSE.

Pages 1070–1103

CHAPTER FOUR

“AN UNHOLY ALLIANCE”

ROCKEFELLER AND HIS PARTY NOW PROPOSE AN OPEN INSTEAD OF A SECRET COMBINATION—“THE PITTSBURG PLAN”—THE SCHEME IS NOT APPROVED BY THE OIL REGIONS BECAUSE ITS CHIEF STRENGTH IS THE REBATE—ROCKEFELLER NOT DISCOURAGED—THREE MONTHS LATER BECOMES PRESIDENT OF NATIONAL REFINERS’ ASSOCIATION—FOUR-FIFTHS OF REFINING INTEREST OF UNITED STATES WITH HIM—OIL REGIONS AROUSED—PRODUCERS’ UNION ORDER DRILLING STOPPED AND A THIRTY DAY SHUT-DOWN TO COUNTERACT FALLING PRICE OF CRUDE—PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ AGENCY FORMED TO ENABLE PRODUCERS TO CONTROL THEIR OWN OIL—ROCKEFELLER OUTGENERALS HIS OPPONENTS AND FORCES A COMBINATION OF REFINERS AND PRODUCERS—PRODUCERS’ ASSOCIATION AND PRODUCERS’ AGENCY SNUFFED OUT—NATIONAL REFINERS’ ASSOCIATION DISBANDS—ROCKEFELLER STEADILY GAINING GROUND.

Pages 1104–1128

xv

CHAPTER FIVE

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS OF A TRUST

EVIDENCE OF REAPPEARANCE OF REBATES SOON AFTER AGREEMENT OF MARCH 25 IS SIGNED—PRINCIPLE THOROUGHLY ESTABLISHED THAT LARGE SHIPPERS SHALL HAVE ADVANTAGES OVER SMALL SHIPPERS IN SPITE OF RAILROADS’ DUTY AS COMMON CARRIERS—AGREEMENT WORKED OUT BY WHICH THREE ROADS ARE TO HAVE FIXED PERCENTAGE OF EASTERN SHIPMENTS—OIL REGIONS ROBBED OF THEIR GEOGRAPHICAL ADVANTAGE—THE RUTTER CIRCULAR—ROCKEFELLER NOW SECRETLY PLANS REALISATION OF HIS DREAM OF PERSONAL CONTROL OF THE REFINING OF OIL—ORGANISATION OF THE CENTRAL ASSOCIATION—H. H. ROGERS’ DEFENCE OF THE PLAN—ROCKEFELLER’S QUIET AND SUCCESSFUL CANVASS FOR ALLIANCES WITH REFINERS—THE REBATE HIS WEAPON—CONSOLIDATION BY PERSUASION OR FORCE—MORE TALK OF A UNITED EFFORT TO COUNTERACT THE MOVEMENT.

Pages 1129–1166

CHAPTER SIX

STRENGTHENING THE FOUNDATIONS

FIRST INTERSTATE COMMERCE BILL—THE BILL PIGEON-HOLED THROUGH EFFORTS OF STANDARD’S FRIENDS—INDEPENDENTS SEEK RELIEF BY PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF PIPE-LINES—PLANS FOR THE FIRST SEABOARD PIPE-LINE—SCHEME FAILS ON ACCOUNT OF MISMANAGEMENT AND STANDARD AND RAILROAD OPPOSITION—DEVELOPMENT OF THE EMPIRE TRANSPORTATION COMPANY AND ITS PROPOSED CONNECTION WITH THE REFINING BUSINESS—STANDARD, ERIE AND CENTRAL FIGHT THE EMPIRE TRANSPORTATION COMPANY AND ITS BACKER, THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD—THE PENNSYLVANIA FINALLY QUITS AFTER A BITTER AND COSTLY WAR—EMPIRE LINE SOLD TO THE STANDARD—ENTIRE PIPE-LINE SYSTEM OF OIL REGIONS NOW IN ROCKEFELLER’S HANDS—NEW RAILROAD POOL BETWEEN FOUR ROADS—ROCKEFELLER PUTS INTO OPERATION SYSTEM OF DRAWBACKS ON OTHER PEOPLE’S SHIPMENTS—HE PROCEEDS RAPIDLY WITH THE WORK OF ABSORBING RIVALS.

Pages 1167–1207

xvi

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE CRISIS OF 1878

A RISE IN OIL—A BLOCKADE IN EXPORTS—PRODUCERS DO NOT GET THEIR SHARE OF THE PROFITS—THEY SECRETLY ORGANISE THE PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ UNION AND PROMISE TO SUPPORT PROPOSED INDEPENDENT PIPE-LINES—ANOTHER INTERSTATE COMMERCE BILL DEFEATED AT WASHINGTON—“IMMEDIATE SHIPMENT”—INDEPENDENTS HAVE TROUBLE GETTING CARS—RIOTS THREATENED—APPEAL TO GOVERNOR HARTRANFT—SUITS BROUGHT AGAINST UNITED PIPE-LINES, PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD AND OTHERS—INVESTIGATIONS PRECIPITATED IN OTHER STATES—THE HEPBURN COMMISSION AND THE OHIO INVESTIGATION—EVIDENCE THAT THE STANDARD IS A CONTINUATION OF THE SOUTH IMPROVEMENT COMPANY—PRODUCERS FINALLY DECIDE TO PROCEED AGAINST STANDARD OFFICIALS—ROCKEFELLER AND EIGHT OF HIS ASSOCIATES INDICTED FOR CONSPIRACY.

Pages 1208–1240

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE COMPROMISE OF 1880

THE PRODUCERS’ SUIT AGAINST ROCKEFELLER AND HIS ASSOCIATES USED BY THE STANDARD TO PROTECT ITSELF—SUITS AGAINST THE TRANSPORTATION COMPANIES ARE DELAYED—TRIAL OF ROCKEFELLER AND HIS ASSOCIATES FOR CONSPIRACY POSTPONED—ALL OF THE SUITS WITHDRAWN IN RETURN FOR AGREEMENTS OF THE STANDARD AND THE PENNSYLVANIA TO CEASE THEIR PRACTICES AGAINST THE PRODUCERS—WITH THIS COMPROMISE THE SECOND PETROLEUM PRODUCERS’ UNION COMES TO AN END—PRODUCERS THEMSELVES TO BLAME FOR NOT STANDING BEHIND THEIR LEADERS—STANDARD AGAIN ENFORCES ORDERS OBJECTIONABLE TO PRODUCERS—MORE OUTBREAKS IN THE OIL REGIONS—ROCKEFELLER HAVING SILENCED ORGANISED OPPOSITION PROCEEDS TO SILENCE INDIVIDUAL COMPLAINT.

Pages 1241–1262

APPENDIX.

Pages 1263–1406

xvii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

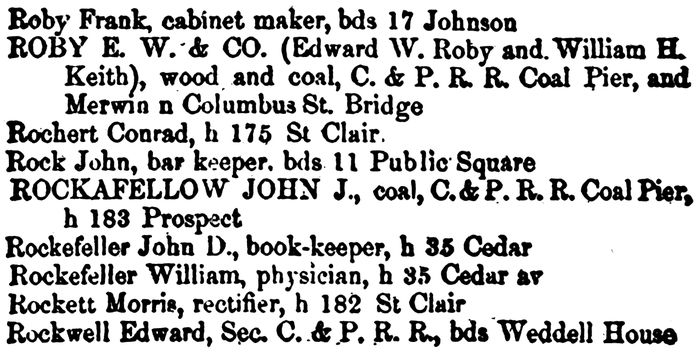

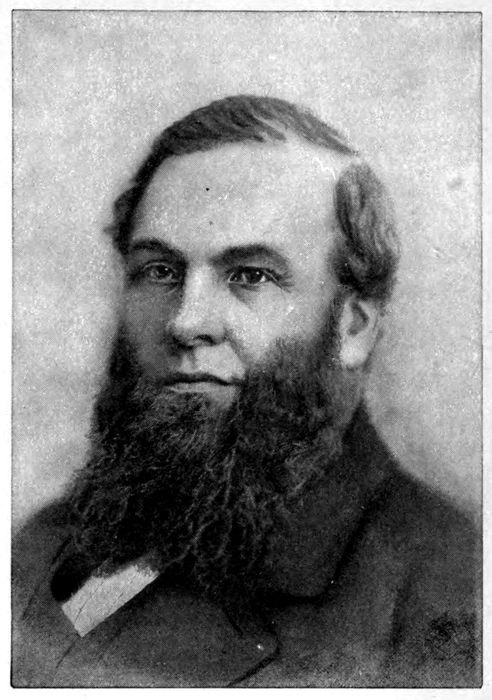

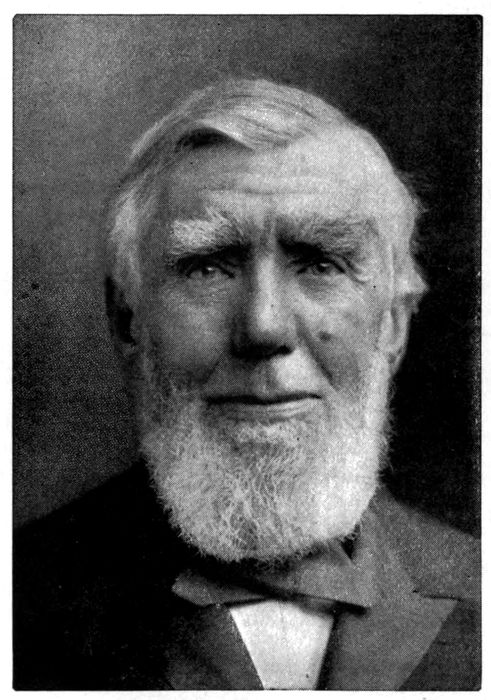

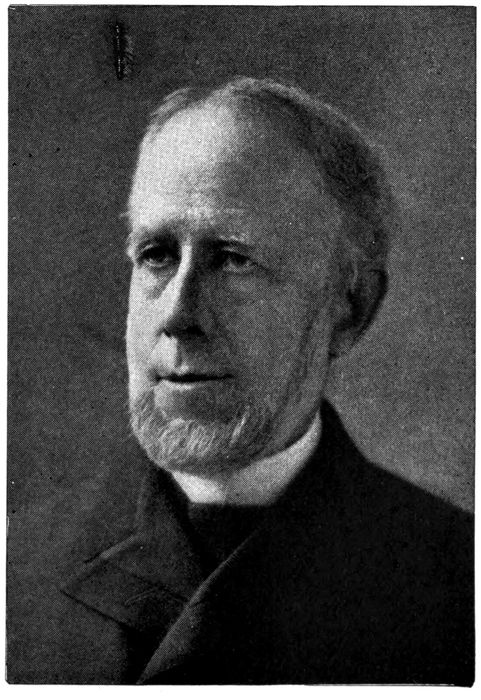

PORTRAIT OF JOHN DAVISON ROCKEFELLER IN 1904

Born July 8, 1839.

FACING PAGE

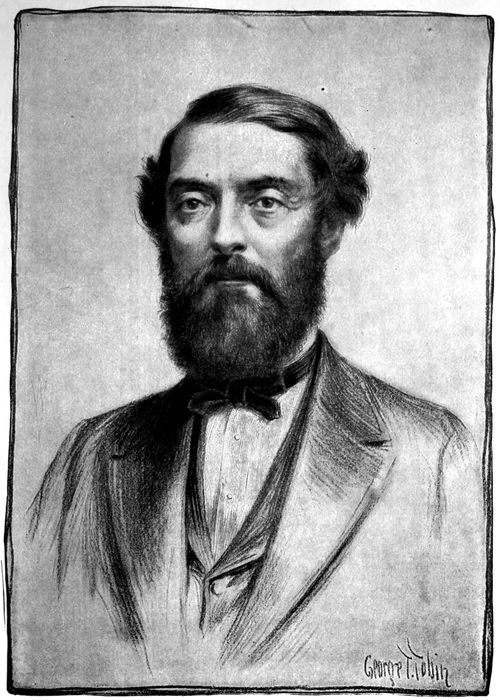

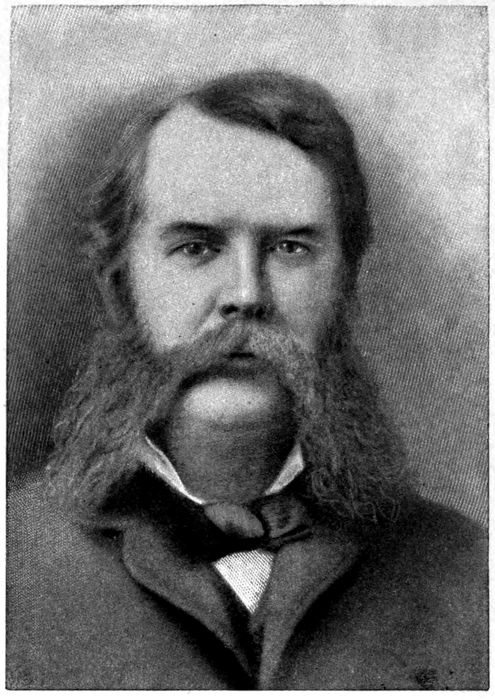

PORTRAIT OF E. L. DRAKE

In 1859 Drake drilled near Titusville, Pennsylvania, the first artesian well put down for petroleum. He is popularly said to have “discovered oil.”

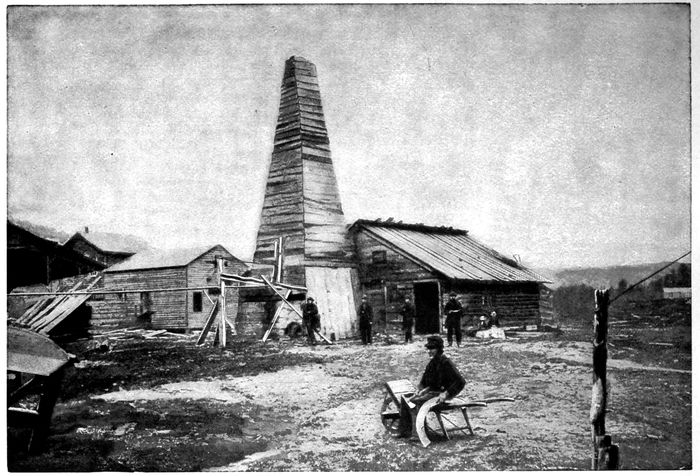

THE DRAKE WELL IN 1859—THE FIRST OIL WELL

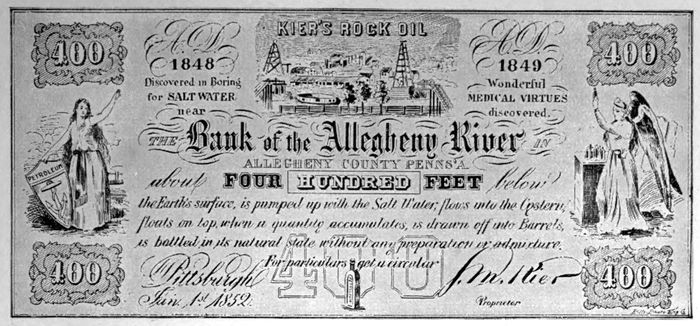

FAC-SIMILE OF A LABEL USED BY S. M. KIER IN ADVERTISING ROCK-OIL OBTAINED IN DRILLING SALT WELLS NEAR TARENTUM, PENNSYLVANIA

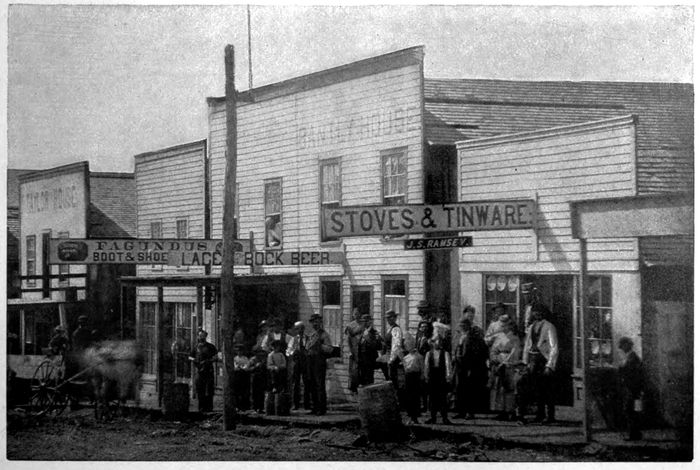

FAGUNDUS—A TYPICAL OIL TOWN

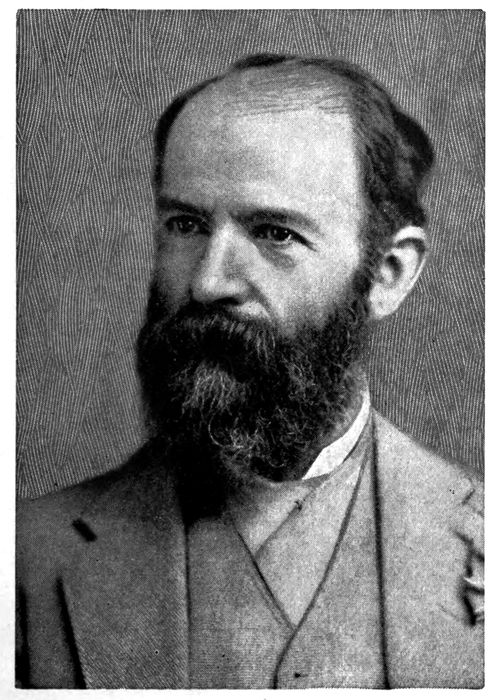

PORTRAIT OF JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IN 1872

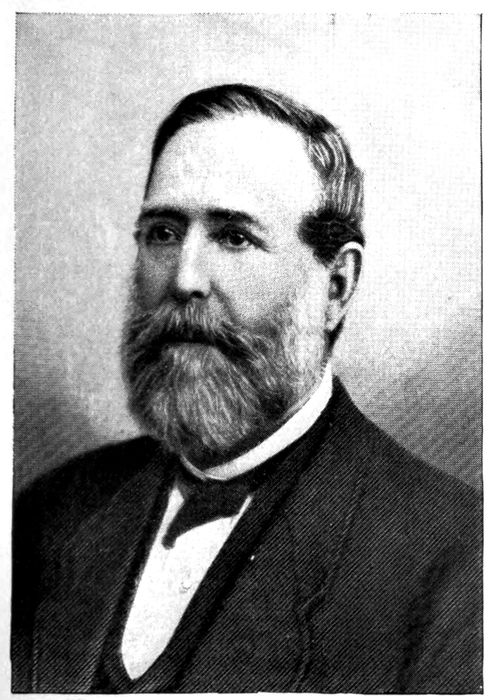

PORTRAIT OF W. G. WARDEN

Secretary of the South Improvement Company.

PORTRAIT OF PETER H. WATSON

President of the South Improvement Company.

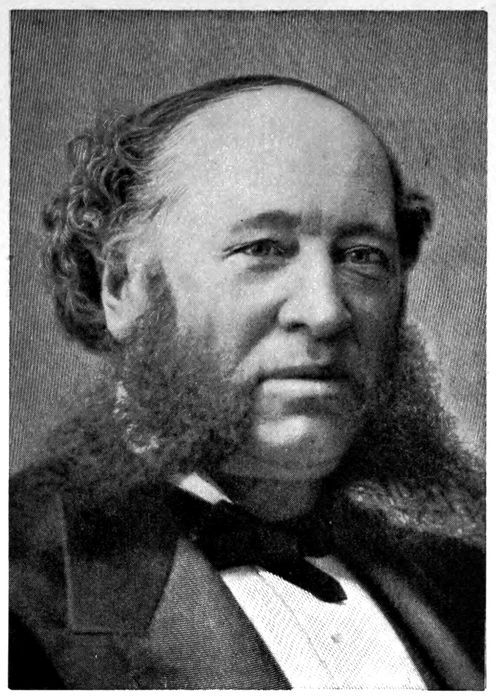

PORTRAIT OF CHARLES LOCKHART

A member of the South Improvement Company, and later of the Standard Oil Company. At his death in 1904 the oldest living oil operator.

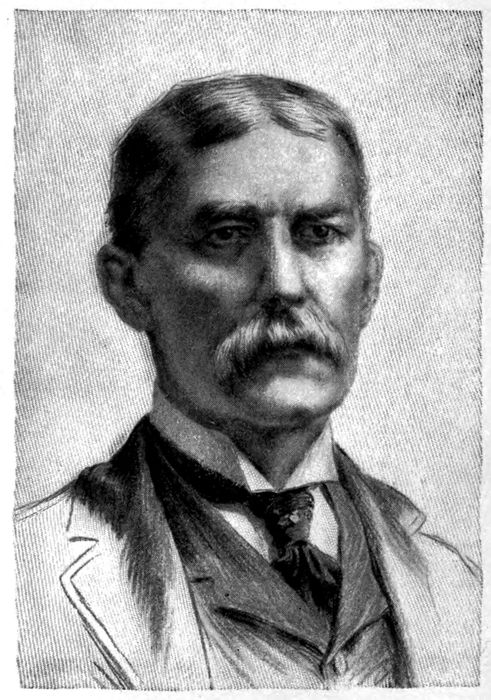

PORTRAIT OF HENRY M. FLAGLER IN 1882

Active partner of John D. Rockefeller in the oil business since 1867. Officer of the Standard Oil Company since its organization in 1870.

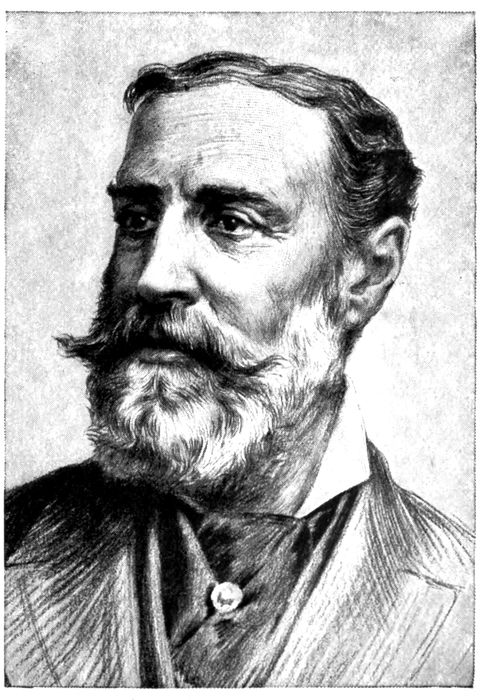

PORTRAIT OF THOMAS A. SCOTT

The contract of the South Improvement Company with the Pennsylvania Railroad was signed by Mr. Scott, then vice-president of the road.

PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT

The contract of the South Improvement Company with the New York Central was signed by Mr. Vanderbilt, then vice-president of the road.

PORTRAIT OF JAY GOULD

President of the Erie Railroad in 1872. Signer of the contract with the South Improvement Company.

xviii

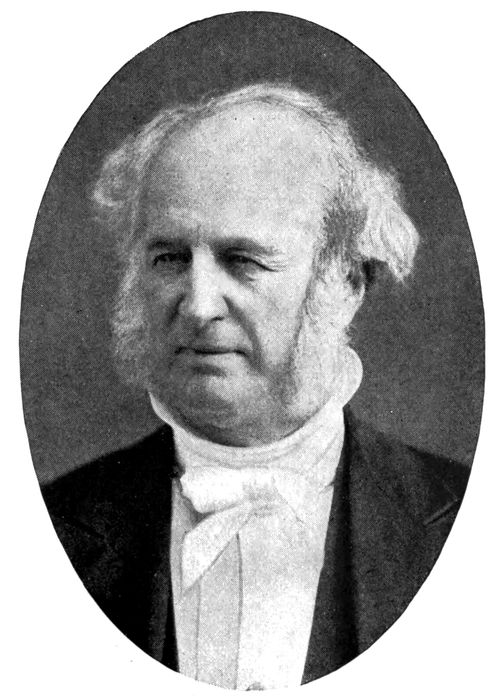

PORTRAIT OF COMMODORE CORNELIUS VANDERBILT

President of the New York Central Railroad when the contract with the South Improvement Company was signed.

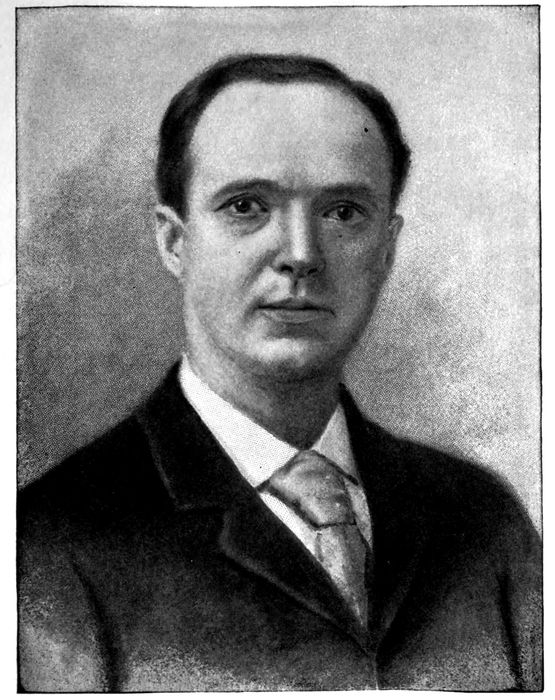

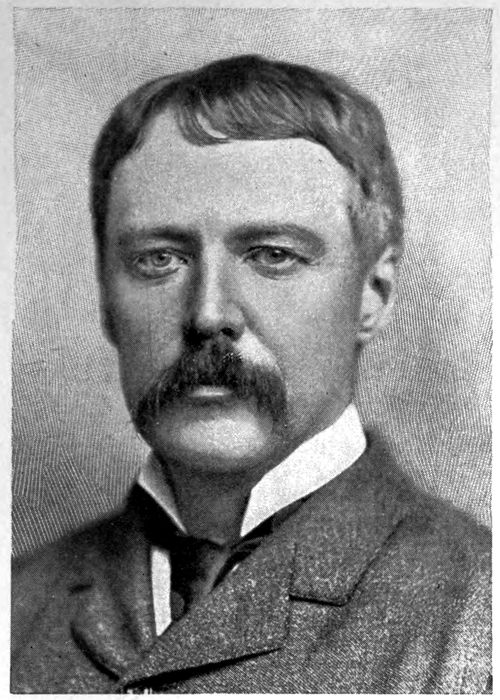

PORTRAIT OF JOHN D. ARCHBOLD IN 1872

Now vice-president of the Standard Oil Company. Mr. Archbold, whose home, in 1872, was in Titusville, Pennsylvania, although one of the youngest refiners of the Creek, was one of the most active and efficient in breaking up the South Improvement Company.

PORTRAIT OF HENRY H. ROGERS IN 1872

Now president of the National Transit Company and a director of the Standard Oil Company. The opposition to the South Improvement Company among the New York refiners was led by Mr. Rogers.

PORTRAIT OF M. N. ALLEN

Independent refiner of Titusville. Editor of the Courier, an able opponent of the South Improvement Company.

PORTRAIT OF JOHN FERTIG

Prominent oil operator. Until 1893 active in Producers’ and Refiners’ Company (independent).

PORTRAIT OF CAPT. WILLIAM HASSON

President of the Petroleum Producers’ Association of 1872.

PORTRAIT OF JOHN L. McKINNEY

Prominent oil operator. Until 1889 an independent. Now member of the Standard Oil Company.

PORTRAIT OF JAMES S. TARR

PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM BARNSDALL

The second oil well on Oil Creek was put down by Mr. Barnsdall.

PORTRAIT OF JAMES S. McCRAY

Owner of the McCray Farm near Petroleum Centre.

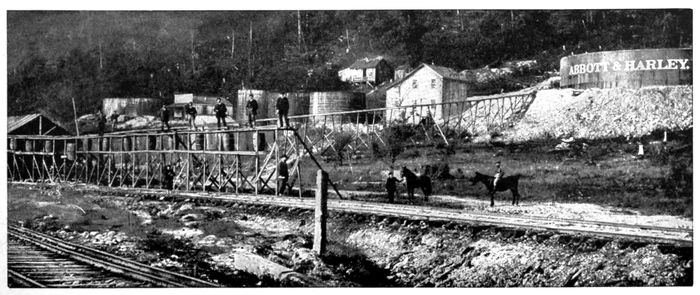

PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM H. ABBOTT

One of the most prominent of the early oil producers, refiners and pipe-line operators.

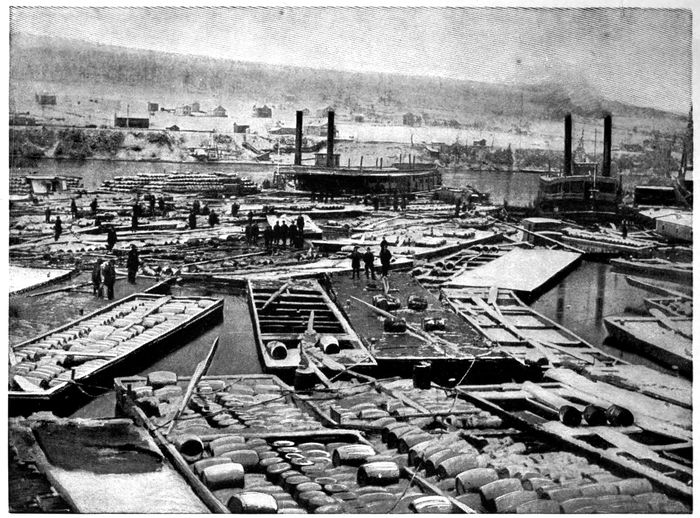

FLEET OF OIL BOATS AT OIL CITY IN 1864

PORTRAIT OF GEORGE H. BISSELL

Founder of the first oil company in the United States.

PORTRAIT OF JONATHAN WATSON

One of the owners of the land on which the first successful well was drilled for oil.

xix

PORTRAIT OF SAMUEL KIER

The first petroleum refined and sold for lighting purpose was made by Mr. Kier in the ’50s in Pittsburg.

PORTRAIT OF JOSHUA MERRILL

The chemist and refiner to whom many of the most important processes now in use in making illuminating and lubricating oils are due.

PORTRAIT OF A. J. CASSATT IN 1877

Third vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad in charge of transportation when first contract was made by that road with the Standard Oil Company.

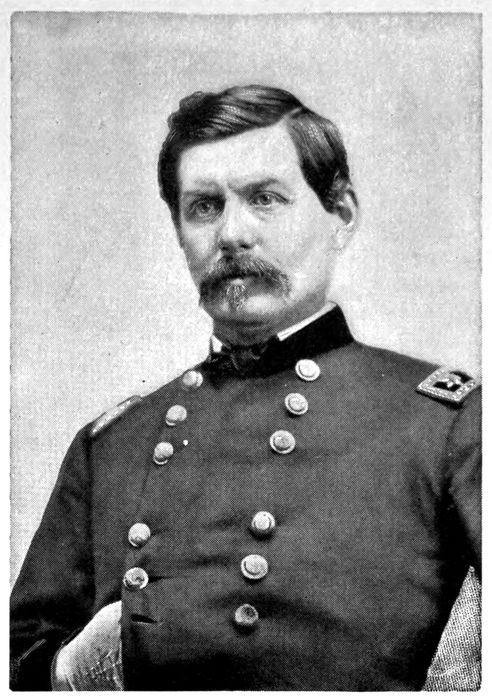

PORTRAIT OF GENERAL GEORGE B. McCLELLAN

President of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad at the time of the South Improvement Company. General McClellan did not sign the contract.

PORTRAIT OF GENERAL JAMES H. DEVEREUX

Who in 1868 as vice-president of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad first granted rebates to Mr. Rockefeller’s firm.

PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH D. POTTS

President of the Empire Transportation Company. Leader in the struggle between the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Standard Oil Company in 1877.

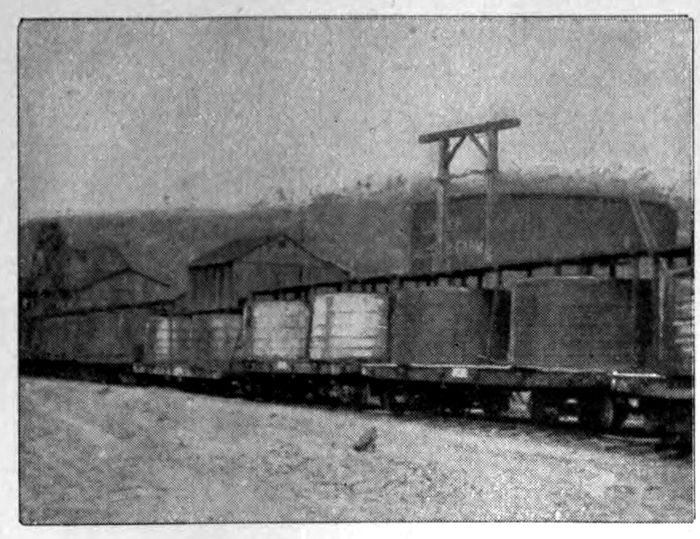

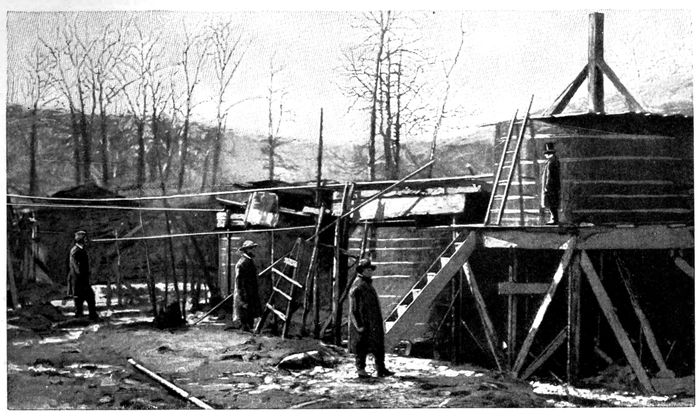

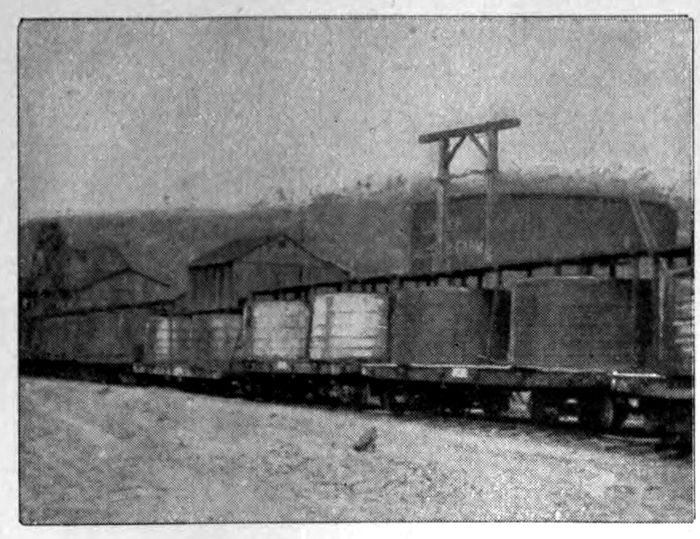

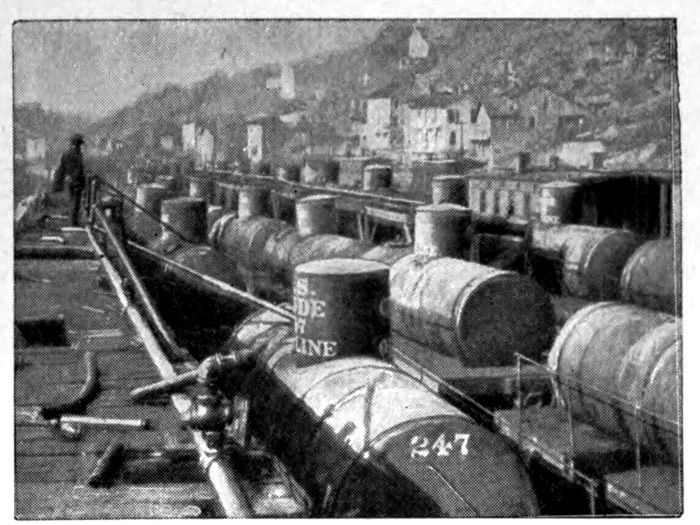

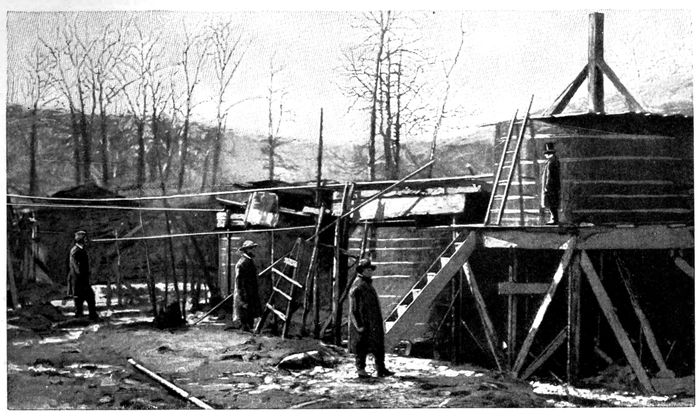

WOODEN CAR TANKS

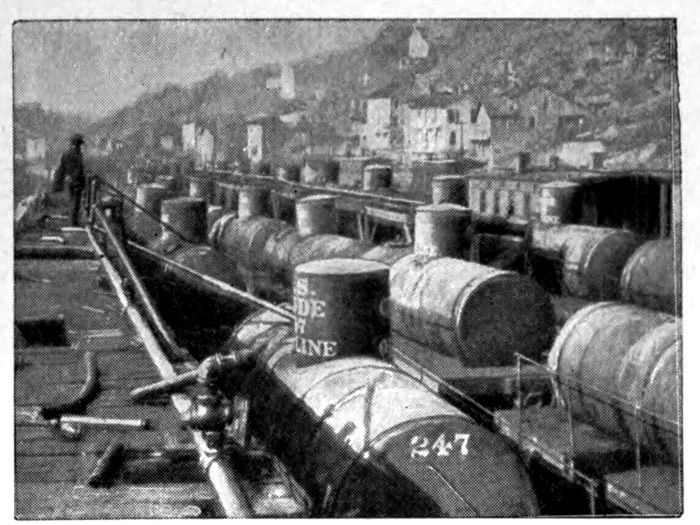

BOILER TANK CARS

WOODEN TANKS FOR STORING OIL

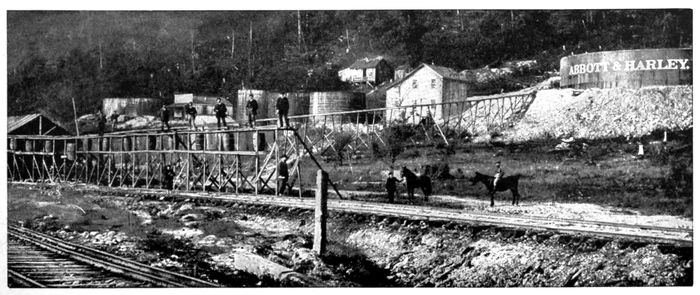

RAILROAD TERMINAL OF AN EARLY PIPE LINE

PORTRAIT OF E. G. PATTERSON

From 1872 to 1880 the chief advocate in the Oil Region of an interstate commerce law. Assisted in drafting the bills of 1876 and 1880. Abandoned the independent interests at the time of the compromise of 1880.

PORTRAIT OF ROGER SHERMAN

Chief counsel of the Petroleum Producers’ Union from 1878 to 1880. From 1880 to 1885 counsel for the Standard Oil Company. From 1885 to his death in 1893 counsel of the allied independents.

PORTRAIT OF BENJ. B. CAMPBELL

President of the Petroleum Producers’ Union from 1878 to 1880. Independent refiner and operator until his death.

PORTRAIT OF JOSIAH LOMBARD

Prominent independent refiner of N. Y. City, whose firm was the only one to keep its contract with the Tidewater Pipe Line Company in 1880.

THE HISTORY OF

THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

1003

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE

THE BIRTH OF AN INDUSTRY

PETROLEUM FIRST A CURIOSITY AND THEN A MEDICINE—DISCOVERY OF ITS REAL VALUE—THE STORY OF HOW IT CAME TO BE PRODUCED IN LARGE QUANTITIES—GREAT FLOW OF OIL—SWARM OF PROBLEMS TO SOLVE—STORAGE AND TRANSPORTATION—REFINING AND MARKETING—RAPID EXTENSION OF THE FIELD OF OPERATION—WORKERS IN GREAT NUMBERS WITH PLENTY OF CAPITAL—COSTLY BLUNDERS FREQUENTLY MADE—BUT EVERY DIFFICULTY BEING MET AND OVERCOME—THE NORMAL UNFOLDING OF A NEW AND WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITY FOR INDIVIDUAL ENDEAVOUR.

One of the busiest corners of the globe at the opening of the year 1872 was a strip of Northwestern Pennsylvania, not over fifty miles long, known the world over as the Oil Regions. Twelve years before this strip of land had been but little better than a wilderness; its chief inhabitants the lumbermen, who every season cut great swaths of primeval pine and hemlock from its hills, and in the spring floated them down the Allegheny River to Pittsburg. The great tides of Western emigration had shunned the spot for years as too rugged and unfriendly for settlement, and yet in twelve years this region avoided by men had been transformed into a bustling trade centre, where towns elbowed each other for place, into which three great trunk railroads had built branches, and every foot of whose soil was fought for by capitalists. It was the discovery and development of a new raw product, petroleum, which had made this change from wilderness to market-place. This product in twelve years had not only peopled a waste place of the earth, it had revolutionised the world’s methods of 1004illumination and added millions upon millions of dollars to the wealth of the United States.

Petroleum as a curiosity, and indeed in a small way as an article of commerce, was no new thing when its discovery in quantities called the attention of the world to this corner of Northwestern Pennsylvania. The journals of many an early explorer of the valleys of the Allegheny and its tributaries tell of springs and streams the surfaces of which were found covered with a thick oily substance which burned fiercely when ignited and which the Indians believed to have curative properties. As the country was opened, more and more was heard of these oil springs. Certain streams came to be named from the quantities of the substance found on the surface of the water, as “Oil Creek” in Northwestern Pennsylvania, “Old Greasy” or Kanawha in West Virginia. The belief in the substance as a cure-all increased as time went on and in various parts of the country it was regularly skimmed from the surface of the water as cream from a pan, or soaked up by woollen blankets, bottled, and peddled as a medicine for man and beast.

Up to the beginning of the 19th century no oil seems to have been obtained except from the surfaces of springs and streams. That it was to be found far below the surface of the earth was discovered independently at various points in Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania by persons drilling for salt-water to be used in manufacturing salt. Not infrequently the water they found was mixed with a dark-green, evil-smelling substance which was recognised as identical with the well-known “rock-oil.” It was necessary to rid the water of this before it could be used for salt, and in many places cisterns were devised in which the brine was allowed to stand until the oil had risen to the surface. It was then run into the streams or on the ground. This practice was soon discovered to be dangerous, so easily did the oil ignite. 1005In several places, particularly in Kentucky, so much oil was obtained with the salt-water that the wells had to be abandoned. Certain of these deserted salt wells were opened years after, when it was found that the troublesome substance which had made them useless was far more valuable than the brine the original drillers sought.

Naturally the first use made of the oil obtained in quantities from the salt wells was medicinal. By the middle of the century it was without doubt the great American medicine. “Seneca Oil” seems to have been the earliest name under which petroleum appeared in the East. It was followed by a large output of Kentucky petroleum sold under the name “American Medicinal Oil.” Several hundred thousand bottles of this oil are said to have been put up in Burkesville, Kentucky, and to have been shipped to the East and to Europe. The point at which the business of bottling petroleum for medicine was carried on most systematically and extensively was Pittsburg. Near that town, at Tarentum in Alleghany County, were located salt wells owned and operated in the forties by Samuel M. Kier. The oil which came up with the salt-water was sufficient to be a nuisance, and Mr. Kier sought a way to use it. Believing it had curative qualities he began to bottle it. By 1850 he had worked up this business until “Kier’s Petroleum, or Rock-Oil” was sold all over the United States. The crude petroleum was put up in eight-ounce bottles wrapped in a circular setting forth in good patent-medicine style its virtues as a cure-all, and giving directions about its use. While it was admitted to be chiefly a liniment it was recommended for cholera morbus, liver complaint, bronchitis and consumption, and the dose prescribed was three teaspoonfuls three times a day! Mr. Kier’s circulars are crowded with testimonials of the efficacy of rock-oil, dated anywhere between 1848 and 1853. Although his trade in this oil was so extensive he was not 1006satisfied that petroleum was useful only as a medicine. He was interested in it as a lubricator and a luminant. That petroleum had the qualities of both had been discovered at more than one point before 1850. More than one mill-owner in the districts where petroleum had been found was using it in a crude way for oiling his machines or lighting his works, but though the qualities of both lubricator and luminant were present, the impurities of the natural oil were too great to make its use general. Mr. Kier seems to have been the first man to have attempted to secure an expert opinion as to the possibility of refining it. In 1849 he sent a bottle of oil to a chemist in Philadelphia, who advised him to try distilling it and burning it in a lamp. Mr. Kier followed the advice, and a five-barrel still which he used in the fifties for refining petroleum is still to be seen in Pittsburg. His trade in the oil he produced at his little refinery was not entirely local, for in 1858 we find him agreeing to sell to Joseph Coffin of New York at 62½ cents a gallon 100 barrels of “carbon oil that will burn in the ordinary coal-oil lamp.”

Although Mr. Kier seems to have done a good business in rock-oil, neither he nor any one else up to this point had thought it worth while to seek petroleum for its own sake. They had all simply sought to utilise what rose before their eyes on springs and streams or came to them mixed with the salt-water for which they drilled. In 1854, however, a man was found who took rock-oil more seriously. This man was George H. Bissell, a graduate of Dartmouth College, who, worn out by an experience of ten years in the South as a journalist and teacher, had come North for a change. At his old college the latest curiosity of the laboratory was shown him—the bottle of rock-oil—and the professor contended that it was as good, or better, than coal for making illuminating oil. Bissell inquired into its origin, and was told that it came 1007from oil springs located in Northwestern Pennsylvania on the farm of a lumber firm, Brewer, Watson and Company. These springs had long yielded a supply of oil which was regularly collected and sold for medicine, and was used locally by mill-owners for lighting and lubricating purposes.

Bissell seems to have been impressed with the commercial possibilities of the oil, for he at once organised a company, the Pennsylvania Rock-Oil Company, the first in the United States, and leased the lands on which these oil springs were located. He then sent a quantity of the oil to Professor Silliman of Yale College, and paid him for analysing it. The professor’s report was published and received general attention. From the rock-oil might be made as good an illuminant as any the world knew. It also yielded gas, paraffine, lubricating oil. “In short,” declared Professor Silliman, “your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive process, they may manufacture very valuable products. It is worthy of note that my experiments prove that nearly the whole of the raw product may be manufactured without waste, and this solely by a well-directed process which is in practice in one of the most simple of all chemical processes.”[1]

The oil was valuable, but could it be obtained in quantities great enough to make the development of so remote a locality worth while? The only method of obtaining it known to Mr. Bissell and his associates in the new company was from the surface of oil springs. Could it be obtained in any other way? There has long been a story current in the Oil Regions that the Pennsylvania Rock-Oil Company received its first notion of drilling for oil from one of those trivial incidents which so often turn the course of human affairs. As the story goes, Mr. Bissell was one day walking down Broadway when he halted to rest in the shade of an 1008awning before a drug store. In the window he saw on a bottle a curious label, “Kier’s Petroleum, or Rock-Oil,” it read, “Celebrated for its wonderful curative powers. A natural Remedy; Produced from a well in Allegheny Co., Pa., four hundred feet below the earth’s surface,” etc. On the label was the picture of an artesian well. It was from this well that Mr. Kier got his “Natural Remedy.” Hundreds of men had seen the label before, for it went out on every one of Mr. Kier’s circulars, but this was the first to look at it with a “seeing eye.” As quickly as the bottle of rock-oil in the Dartmouth laboratory had awakened in Mr. Bissell’s mind the determination to find out the real value of the strange substance, the label gave him the solution of the problem of getting oil in quantities—it was to bore down into the earth where it was stored, and pump it up.

Professor Silliman made his report to the Pennsylvania Rock-Oil Company in 1855, but it was not until the spring of 1858 that a representative of the organisation, which by this time had changed hands and was known as the Seneca Oil Company, was on the ground with orders to find oil. The man sent out was a small stockholder in the company, Edwin L. Drake, “Colonel” Drake as he was called. Drake had had no experience to fit him for his task. A man forty years of age, he had spent his life as a clerk, an express agent, and a railway conductor. His only qualifications were a dash of pioneer blood and a great persistency in undertakings which interested him. Whether Drake came to Titusville ordered to put down an artesian well or not is a mooted point. His latter-day admirers claim that the idea was entirely his own. It seems hardly credible that men as intelligent as Professor Silliman, Mr. Bissell, and others interested in the Pennsylvania Rock-Oil Company, should not have taken means of finding out how the familiar “Kier’s Rock-Oil” was obtained. Professor Silliman at least must have known of the quantities of oil which had been obtained in different states in drilling salt wells; indeed, in his report (see Appendix, Number 1) he speaks of “wells sunk for the purpose of accumulating the product.” In the “American Journal of Science” for 1840—of which he was one of the editors—is an account of a famous oil well struck near Burkesville, Kentucky, about 1830, when drilling for salt. It seems probable that the idea of seeking oil on the lands leased by the Petroleum Rock-Oil Company by drilling artesian wells had been long discussed by the gentlemen interested in the venture, and that Drake came to Titusville with instructions to put down a well. It is certain, at all events, that he was soon explaining to his superiors at home the difficulty of getting a driller, an engine-house and tools, and that he was employing the interval in trying to open new oil springs and make the old ones more profitable.

E. L. DRAKE

In 1859 Drake drilled near Titusville, Pennsylvania, the first artesian well put down for petroleum. He is popularly said to have “discovered oil.”

In 1859 Drake drilled near Titusville, Pennsylvania, the first artesian well put down for petroleum. He is popularly said to have “discovered oil.”

1009The task before Drake was no light one. The spot to which he had been sent was Titusville, a lumberman’s hamlet on Oil Creek, fourteen miles from where that stream joins the Allegheny River. Its chief connection with the outside world was by a stage to Erie, forty miles away. This remoteness from civilisation and Drake’s own ignorance of artesian wells, added to the general scepticism of the community concerning the enterprise, caused great difficulty and long delays. It was months before Drake succeeded in getting together the tools, engine and rigging necessary to bore his well, and before he could get a driller who knew how to manipulate them, winter had come, and he had to suspend operations. People called him crazy for sticking to the enterprise, but that had no effect on him. As soon as spring opened he borrowed a horse and wagon and drove over a hundred miles to Tarentum, where Mr. Kier was still pumping his salt wells, and was either bottling or refining the oil which came up with the brine. Here Drake hoped to find a driller. 1010He brought back a man, and after a few months more of experiments and accidents the drill was started. One day late in August, 1859, Titusville was electrified by the news that Drake’s Folly, as many of the onlookers had come to consider it, had justified itself. The well was full of oil. The next day a pump was started, and twenty-five barrels of oil were gathered.

There was no doubt of the meaning of the Drake well in the minds of the people of the vicinity. They had long ago accepted all Professor Silliman had said of the possibilities of petroleum, and now that they knew how it could be obtained in quantity, the whole countryside rushed out to obtain leases. The second well in the immediate region was drilled by a Titusville tanner, William Barnsdall—an Englishman who at his majority had come to America to make his fortune. He had fought his way westward, watching always for his chance. The day the Drake well was struck he knew it had come. Quickly forming a company he began to drill a well. He did not wait for an engine, but worked his drill through the rock by a spring pole.[2] It took three months, and cost $3,000 to do it, but he had his reward. On February 1, 1860, he struck oil—twenty-five barrels a day—and oil was selling at eighteen dollars a barrel. In five months the English tanner had sold over $16,000 worth of oil.

THE DRAKE WELL IN 1859. THE FIRST OIL WELL.

1011A lumberman and merchant of the village, who long had had faith in petroleum if it could be had in quantity, Jonathan Watson, one of the firm of Brewer, Watson and Company, whose land the Pennsylvania Rock-Oil Company had leased, mounted his horse as soon as he heard of the Drake well, and, riding down the valley of Oil Creek, spent the day in leasing farms. He soon had the third well of the region going down, this too by a spring pole. This well started off in March at sixty gallons a minute, and oil was selling at sixty cents a gallon. In two years the farm where this third well was struck had produced 165,000 barrels of oil.

Working an unfriendly piece of land a few miles below the Drake well lived a man of thirty-five. Setting out for himself at twenty-two, he had won his farm by the most dogged efforts, working in sawmills, saving his earnings, buying a team, working it for others until he could take up a piece of land, hoarding his savings here. For what? How could he know? He knew well enough when Drake struck oil, and hastened out to buy a share in a two-acre farm. He sold it at a profit, and with the money put down a well, from which he realised $70,000. A few years later the farm he had slaved to win came into the field. In 1871 he refused a million dollars for it, and at one time he had stored there 200,000 barrels of oil.

A young doctor who had buried himself in the wilderness saw his chance. For a song he bought thirty-eight acres on the creek, six miles below the Drake well, and sold half of it for the price he had paid to a country storekeeper and lumberman of the vicinity, one Charles Hyde. Out of this thirty-eight acres millions of dollars came; one well alone—the Mapleshade—cleared one and one-half millions.

On every rocky farm, in every poor settlement of the 1012region, was some man whose ear was attuned to Fortune’s call, and who had the daring and the energy to risk everything he possessed in an oil lease. It was well that he acted at once; for, as the news of the discovery of oil reached the open, the farms and towns of Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania poured out a stream of ambitious and vigorous youths, eager to seize what might be there for them, while from the East came men with money and business experience, who formed great stock companies, took up lands in parcels of thousands of acres, and put down wells along every rocky run and creek, as well as over the steep hills. In answer to their drill, oil poured forth in floods. In many places pumping was out of the question; the wells flowed 2,000, 3,000, 4,000 barrels a day—such quantities of it that at the close of 1861 oil which in January of 1860 was twenty dollars a barrel had fallen to ten cents.

Here was the oil, and in unheard-of quantities, and with it came all the swarm of problems which a discovery brings. The methods Drake had used were crude and must be improved. The processes of refining were those of the laboratory and must be developed. Communication with the outside world must be secured. Markets must be built up. Indeed, a whole new commercial machine had to be created to meet the discovery. These problems were not realised before the region teemed with men to wrestle with them—men “alive to the instant need of things.” They had to begin with so simple and elementary a matter as devising something to hold the oil. There were not barrels enough to be bought in America, although turpentine barrels, molasses barrels, whiskey barrels—every sort of barrel and cask—were added to new ones made especially for oil. Reservoirs excavated in the earth and faced with logs and cement, and box-like structures of planks or logs were tried at first but were not satisfactory. A young Iowa school teacher and farmer, visiting 1013at his home in Erie County, went to the region. Immediately he saw his chance. It was to invent a receptacle which would hold oil in quantities. Certain large producers listened to his scheme and furnished money to make a trial tank. It was a success, and before many months the school teacher was buying thousands of feet of lumber, employing scores of men, and working them and himself—day and night. For nearly ten years he built these wooden tanks. Then seeing that iron tanks—huge receptacles holding thousands of barrels where his held hundreds—were bound to supersede him, he turned, with the ready adaptability which characterised the men of the region, to producing oil for others to tank.

After the storing problem came that of transportation. There was one waterway leading out—Oil Creek, as it had been called for more than a hundred years,—an uncertain stream running the length of the narrow valley in which the oil was found, and uniting with the Allegheny River at what is now known as Oil City. From this junction it was 132 miles to Pittsburg and a railroad. Besides this waterway were rough country roads leading to the railroads at Union City, Corry, Erie and Meadville. There was but one way to get the oil to the bank of Oil Creek or to the railroads, and that was by putting it into barrels and hauling it. Teamsters equipped for this service seemed to fall from the sky. The farms for a hundred miles around gave up their boys and horses and wagons to supply the need. It paid. There were times when three and even four dollars a barrel were paid for hauling five or ten miles. It was not too much for the work. The best roads over which they travelled were narrow, rough, unmade highways, mere openings to the outer world, while the roads to the wells they themselves had to break across fields and through forests. These roads were made almost impassable by the great number of heavily freighted wagons travelling over them. From the big wells a constant 1014procession of teams ran, and it was no uncommon thing for a visitor to the Oil Regions to meet oil caravans of a hundred or more wagons. Often these caravans were held up for hours by a dangerous mud-hole into which a wheel had sunk or a horse fallen. If there was a possible way to be made around the obstruction it was taken, even if it led through a farmer’s field. Indeed, a sort of guerilla warfare went on constantly between the farmers and the teamsters. Often the roads became impassable, so that new ones had to be broken, and not even a shot-gun could keep the driver from going where the passage was least difficult. The teamster, in fact, carried a weapon which few farmers cared to face, his terrible “black snake,” as his long, heavy black whip was called. The man who had once felt the cruel lash of a “black snake” around his legs did not often oppose the owner.

With the wages paid him the teamster could easily become a kind of plutocrat. One old producer tells of having a teamster in his employ who for nine weeks drew only enough of his earnings to feed himself and horses. He slept in his wagon and tethered the team. At the end of the time he “thought he’d go home for a clean shirt” and asked for a settlement. It was found that he had $1,900 to his credit. The story is a fair illustration both of the habits and the earnings of the Oil Creek teamsters. Indispensable to the business they became the tyrants of the region—working and brawling as suited them, a genius not unlike the flatboat-men who once gave colour to life on the Mississippi, or the cowboys who make the plains picturesque to-day. Bad as their reputation was, many a man found in their ranks the start which led later to wealth and influence in the oil business. One of the shrewdest, kindest, oddest men the Oil Regions ever knew, Wesley Chambers, came to the top from the teamster class. He had found his way to the creek after eight years of unsuccessful gold-hunting in California. “There’s my chance,” he said, 1015when he saw the lack of teams and boats, and he set about organising a service for transporting oil to Pittsburg. In a short time he was buying horses of his own and building boats. Wide-awake to actualities, he saw a few years later that the teamster and the boat were to be replaced by the pipe-line and the railroad, and forestalled the change by becoming a producer.

In this problem of transportation the most important element after the team was Oil Creek and the flatboat. A more uncertain stream never ran in a bed. In the summer it was low, in the winter frozen; now it was gorged with ice, now running mad over the flats. The best service was gotten out of it in time of low water through artificial freshets. Milldams, controlled by private parties, were frequent along the creek and its tributaries. By arrangement these dams were cut on a certain day or days of the week, usually Friday, and on the flood or freshet the flatboats loaded with barrels of oil were floated down stream. The freshet was always exciting and perilous and frequently disastrous. From the points where they were tied up the boatmen watched the coming flood and cut themselves loose the moment after its head had passed them. As one fleet after another swung into the roaring flood the danger of collision and jams increased. Rare indeed was the freshet when a few wrecks did not lie somewhere along the creek, and often scores lay piled high on the bank—a hopeless jam of broken boats and barrels, the whole soaked in petroleum and reeking with gas and profanity. If the boats rode safely through to the river, there was little further danger.

The Allegheny River traffic grew to great proportions—fully 1,000 boats and some thirty steamers were in the fleet, and at least 4,000 men. This traffic was developed by men who saw here their opportunity of fortune, as others had seen it in drilling or teaming. The foremost of these men 1016was an Ohio River captain, driven northward by the war, one J. J. Vandergrift. Captain Vandergrift had run the full gamut of river experiences from cabin-boy to owner and commander of his own steamers. The war stopped his Mississippi River trade. Fitting up one of his steamers as a gun-boat, he turned it over to Commodore Foote and looked for a new stream to navigate. From the Oil Region at that moment the loudest cry was for barrels. He towed 4,000 empty casks up the river, saw at once the need of some kind of bulk transportation, took his hint from a bulk-boat which an ingenious experimenter was trying, ordered a dozen of them built, towed his fleet to the creek, bought oil to fill them, and then returned to Pittsburg to sell his cargo. On one alone he made $70,000.

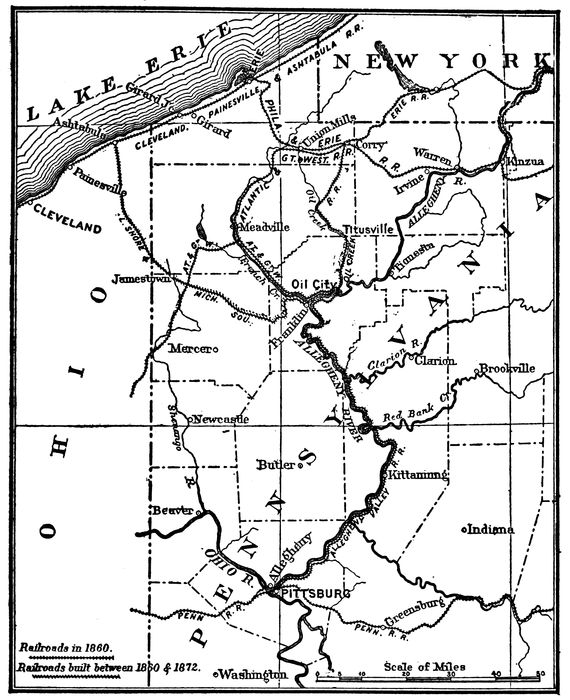

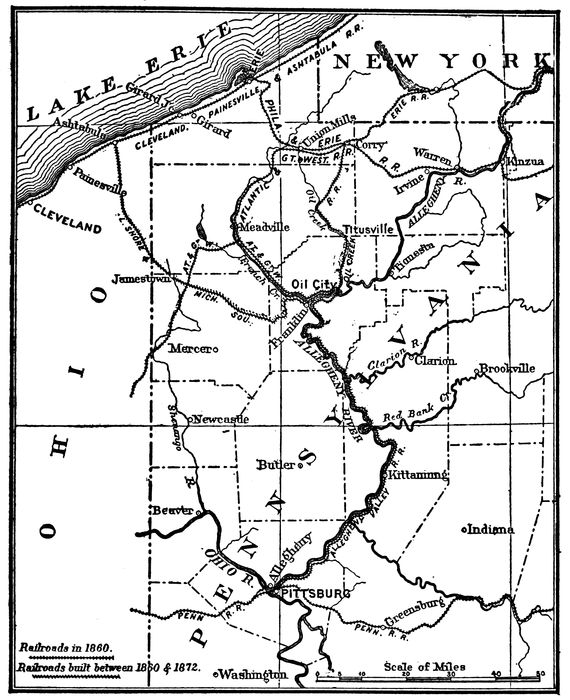

But the railroad soon pressed the river hard. At the time of the discovery of oil three lines, the Philadelphia and Erie, the Buffalo and Erie (now the Lake Shore), connecting with the Central, and the Atlantic and Great Western, connecting with the Erie, were within teaming distance of the region. The points at which the Philadelphia and Erie road could be reached were Erie, forty miles from Titusville, Union City, twenty-two miles, and Corry, sixteen miles. The Buffalo and Erie was reached at Erie. The Atlantic and Great Western was reached at Meadville, Union City and Corry, and the distances were twenty-eight, twenty-two and sixteen miles, respectively. Erie was the favourite shipping point at first, as the wagon road in that direction was the best. The amount of freight the railroads carried the first year of the business was enormous. Of course connecting lines were built as rapidly as men could work. By the beginning of 1863 the Oil Creek road, as it was known, had reached Titusville from Corry. This gave an eastern connection by both the Philadelphia and Erie and the Atlantic and Great Western, but as the latter was constructing a branch from Meadville to 1017Franklin, the Oil Creek road became the feeder of the former principally. Both of these roads were completed to Oil City by 1865.

The railroads built, the vexatious, time-taking, and costly problem of getting the oil from the well to the shipping point still remained. The teamster was still the tyrant of the business. His day was almost over. He was to fall before the pipe-line. The feasibility of carrying oil in pipes was discussed almost from the beginning of the oil business. Very soon after the Drake well was struck oil men began to say that the natural way to get this oil from the wells to the railroads was through pipes. In many places gravity would carry it; where it could not, pumps would force it. The belief that this could be done was so strong that as early as February, 1862, a company was incorporated in Pennsylvania for carrying oil in pipes or tubes from any point on Oil Creek to its mouth or to any station on the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad. This company seems never to have done more than get a charter. In 1863 at least three short pipe-lines were put into operation. The first of these was a two–inch pipe, through which distillate was pumped a distance of three miles from the Warren refinery at Plumer to Warren’s Landing on the Allegheny River. The one which attracted the most attention was a line two and one-half miles in length carrying crude oil from the Tarr farm to the Humboldt refinery at Plumer. Various other experiments were made, both gravity and pumps being trusted for propelling the oil, but there was always something wrong; the pipes leaked or burst, the pumps were too weak; shifting oil centres interrupted experiments which might have been successful. Then suddenly the man for the need appeared, Samuel Van Syckel. He came to the creek in 1864 with some money, hoping to make more. He handled quantities of oil produced at Pithole, several miles from a shipping point, and saw his profits eaten up 1018by teamsters. Their tyranny aroused his ire and his wits and he determined to build a pipe-line from the wells to the railroad. He was greeted with jeers, but he went doggedly ahead, laid a two–inch pipe, put in three relay pumps, and turned in his oil. From the start the line was a success, carrying eighty barrels of oil an hour. The day that the Van Syckel pipe-line began to run oil a revolution began in the business. After the Drake well it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions.

The teamsters saw its meaning first and turned out in fury, dragging the pipe, which was for the most part buried, to the surface, and cutting it so that the oil would be lost. It was only by stationing an armed guard that they were held in check. A second line of importance, that of Abbott and Harley, suffered even more than that of Van Syckel. The teamsters did more than cut the pipe; they burned the tanks in which oil was stored, laid in wait for employees, threatened with destruction the wells which furnished the oil, and so generally terrorised the country that the governor of the state was called upon in April, 1866, to protect the property and men of the lines. The day of the teamster was over, however, and the more philosophical of them accepted the situation; scores disappeared from the region, and scores more took to drilling. They died hard, and the cutting and plugging of pipe-lines was for years a pastime of the remnant of their race.

If the uses to which oil might be put and the methods for manufacturing it had not been well understood when the Drake well was struck, there would have been no such imperious demand as came for the immediate opening of new territory and developing methods of handling and carrying it on a large scale. But men knew already what the oil was good for, and, in a crude way, how to distil it. The process of distillation also was free to all. The essential 1019apparatus was very simple—a cast-iron still, usually surrounded by brickwork, a copper worm, and two tin- or zinc-lined tanks. The still was filled with crude oil, which was subjected to a high enough heat to vapourise it. The vapour passed through a cast-iron goose-neck fitted to the top of the still into the copper worm, which was immersed in water. Here the vapour was condensed and passed into the zinc-lined tank. This product, called a distillate, was treated with chemicals, washed with water, and run off into the tin-lined tank, where it was allowed to settle. Anybody who could get the apparatus could “make oil,” and many men did—badly, of course, to begin with, and with an alarming proportion of waste and explosions and fires, but with experience they learned, and some of the great refineries of the country grew out of these rude beginnings.

Luckily not all the men who undertook the manufacturing of petroleum in these first days were inexperienced. The chemists to whom are due chiefly the processes now used—Atwood, Gessner, and Merrill—had for years been busy making oils from coal. They knew something of petroleum, and when it came in quantities began at once to adapt their processes to it. Merrill at the time was connected with Samuel Downer, of Boston, in manufacturing oil from Trinidad pitch and from coal bought in Newfoundland. The year oil was discovered Mr. Downer distilled 7,500 tons of this coal, clearing on it at least $100,000. As soon as petroleum appeared he and Mr. Merrill saw that here was a product which was bound to displace their coal, and with courage and promptness they prepared to adapt their works. In order to be near the supply they came to Corry, fourteen miles from the Drake well, and in 1862 put up a refinery which cost $250,000. Here were refined thousands of barrels of oil, most of which was sent to New York for export. To the Boston works the firm sent crude, which was manufactured for the home trade and 1020for shipping to California and Australia. The processes used in the Downer works at this early day were in all essentials the same as are used to-day.

In 1865 William Wright, after a careful study of “Petrolia,” as the Oil Regions were then often called, published with Harper and Brothers an interesting volume in which he devotes a chapter to “Oil Refining and Refiners.” Mr. Wright describes there not only the Downer works at Corry, but a factory which if much less important in the development of the Oil Regions held a much larger place in its imagination. This was the Humboldt works at Plumer. In 1862 two Germans, brothers, the Messrs. Ludovici, came to the oil country and, choosing a spot distant from oil wells, main roads, or water courses, erected an oil refinery which was reported to have cost a half million dollars. The works were built in a way unheard of then and uncommon now. The foundations were all of cut stone. The boiler and engines were of the most expensive character. A house erected in connection with the refinery was said to have been finished in hard wood with marble mantels, and furnished with rich carpets, mirrors, and elaborate furniture. The lavishness of the Humboldt refinery and the formality with which its business was conducted were long a tradition in the Oil Regions. Of more practical moment are the features of the refinery which Mr. Wright mentions: one is that the works had been so planned as to take advantage of the natural descent of the ground so that the oil would pass from one set of vessels to another without using artificial power, and the other that the supply of crude oil was obtained from the Tarr farm three miles away, being forced by pumps, through pipes, over the hills.

Mr. Wright found some twenty refineries between Titusville and Oil City the year of his visit, 1865. In several factories that he visited they were making naphtha, gasoline, and 1021benzine for export. Three grades of illuminating oils—“prime white,” “standard white,” and “straw colour”—were made everywhere; paraffine, refined to a pure white article like that of to-day, was manufactured in quantities by the Downer works; and lubricating oils were beginning to be made.

As men and means were found to put down wells, to devise and build tanks and boats and pipes and railroads for handling the oil, to adapt and improve processes for manufacturing, so men were found from the beginning of the oil business to wrestle with every problem raised. They came in shoals, young, vigorous, resourceful, indifferent to difficulties, greedy for a chance, and with each year they forced more light and wealth from the new product. By the opening of 1872 they had produced nearly 40,000,000 barrels of oil, and had raised their product to the fourth place among the exports of the United States, over 152,000,000 gallons going abroad in 1871, a percentage of the production which compares well with what goes to-day.[3] As for the market, they had developed it until it included almost every country of the earth—China, the East and West Indies, South America and Africa. Over forty different European ports received refined oil from the United States in 1871. Nearly a million gallons were sent to Syria, about a half million to Egypt, about as much to the British West Indies, and a quarter of a million to the Dutch East Indies. Not only were illuminating oils being exported. In 1871 nearly seven million gallons of naphtha, benzine, and gasoline were sent abroad, and it became evident now for the first time that a valuable trade in lubricants made from petroleum was possible. A discovery by Joshua Merrill of the Downer works opened this new source of wealth to the industry. Until 1869 the impossibility of deodorising petroleum had prevented its use largely as a lubricant, but in that year 1022Mr. Merrill discovered a process by which a deodorised lubricating oil could be made. He had both the apparatus for producing the oil and the oil itself patented. The oil was so favourably received that the market sale by the Downer works was several hundred per cent. greater in a single year than the firm had ever sold before.

The oil field had been extended from the valley of Oil Creek and its tributaries down the Allegheny River for fifty miles and probably covered 2,000 square miles. The early theory that oil followed the streams had been exploded, and wells were now drilled on the hills. It was known, too, that if oil was found in the first sand struck in the drilling, it might be found still lower in a second or third sand. The Drake well had struck oil at 69½ feet, but wells were now drilled as deep as 1,600 feet. The extension of the field, the discovery that oil was under the hills as well as under streams, and to be found in various sands, had cost enormously. It had been done by “wild-catting,” as putting down experimental wells was called, by following superstitions in locating wells, such as the witch-hazel stick, or the spiritualistic medium, quite as much as by studying the position of wells in existence and calculating how oil belts probably ran. As the cost of a well was from $3,000 to $8,000,[4] according to its location, and as 4,374 of the 5,560 wells drilled in the first ten years of the business (1859 to 1869) were “dry-holes,” or were abandoned as unprofitable, something of the daring it took to operate on small means, as most producers did in the beginning, is evident. But they loved the game, and every man of them would stake his last dollar on the chance of striking oil.

With the extension of the field rapid strides had been made in tools, in rigs, in all of the various essentials of drilling a well. They had learned to use torpedoes to open up hard rocks, 1023naphtha to cut the paraffine which coated the sand and stopped the flow of oil, seed bags to stop the inrush of a stream of water. They lost their tools less often, and knew better how to fish for them when they did. In short, they had learned how to put down and care for oil wells.

Equal advances had been made in other departments, fewer cars were loaded with barrels, tank cars for carrying in bulk had been invented. The wooden tank holding 200 to 1,200 barrels had been rapidly replaced by the great iron tank holding 20,000 or 30,000 barrels. The pipe-lines had begun to go directly to the wells instead of pumping from a general receiving station, or “dump,” as it was called, thus saving the tedious and expensive operation of hauling. From beginning to end the business had been developed, systematised, simplified.

Most important was the simplification of the transportation problem by the development of pipe-lines. By 1872 they were the one oil gatherer. Several companies were carrying on the pipe-line business, and two of them had acquired great power in the Oil Regions because of their connection with trunk lines. These were the Empire Transportation Company and the Pennsylvania Transportation Company. The former, which had been the first business organisation to go into the pipe-line business on a large scale, was a concern which had appeared in the Oil Regions not over six months before Van Syckel began to pump oil. The Empire Transportation Company had been organised in 1865 to build up an east and west freight traffic via the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad, a new line which had just been leased by the Pennsylvania. Some ten railroads connected in one way or another with the Philadelphia and Erie, forming direct routes east and west. In spite of their evident community of interest these various roads were kept apart by their jealous fears of one another. Each insisted on its own time-table, its own rates, 1024its own way of doing things. The shipper via this route must make a separate bargain with each road and often submit to having his freight changed at terminals from one car to another because of the difference of gauge. The Empire Transportation Company undertook to act as a mediator between the roads and the shipper, to make the route cheap, fast, and reliable. It proposed to solicit freight, furnish its own cars and terminal facilities, and collect money due. It did not make rates, however; it only harmonised those made by the various branches in the system. It was to receive a commission on the business secured, and a rental for the cars and other facilities it furnished.

It was a difficult task the new company undertook, but it had at its head a remarkable man to cope with difficulties. This man, Joseph D. Potts, was in 1865 thirty-six years old. He had come of a long and honourable line of iron-masters of the Schuylkill region of Pennsylvania, but had left the great forge towns with which his ancestors had been associated—Pottstown, Glasgow Forge, Valley Forge—to become a civil engineer. His profession had led him to the service of the Pennsylvania Railroad, where he had held important positions in connection with which he now undertook the organisation of the Empire Transportation Company. Colonel Potts—the title came from his service in the Civil War—possessed a clear and vigorous mind; he was far-seeing, forceful in execution, fair in his dealings. To marked ability and integrity he joined a gentle and courteous nature.

The first freight which the Empire Transportation Company attacked after its organisation was oil. The year was a great one for the Oil Regions, the year of Pithole. In January there had suddenly been struck on Pithole Creek in a wilderness six miles from the Allegheny River a well, located with a witch-hazel twig, which produced 250 barrels a day—and oil was selling at eight dollars a barrel! Wells followed in 1025rapid succession. In less than ten months the field was doing over 10,000 barrels a day. This sudden flood of oil caused a tremendous excitement. Crowds of speculators and investors rushed to Pithole from all over the country. The Civil War had just closed, soldiers were disbanding, and hundreds of them found their way to the new oil field. In six weeks after the first well was struck Pithole was a town of 6,000 inhabitants. In less than a year it had fifty hotels and boardinghouses; five of these hotels cost $50,000 or more each. In six months after the first well the post-office of Pithole was receiving upwards of 10,000 letters per day and was counted third in size in the state—Philadelphia, Pittsburg, and Pithole being the order of rank. It had a daily paper, churches, all the appliances of a town.

The handling of the great output of oil from the Pithole field was a serious question. There seemed not enough cars in the country to carry it and shippers resorted to every imaginable trick to get accommodations. When the agent of the Empire Transportation Company opened his office in June, 1865, and demonstrated his ability to furnish cars regularly and in large numbers, trade rapidly flowed to him. Now the Empire agency had hardly been established when the Van Syckel pipe-line began to carry oil from Pithole to the railroad. Lines began to multiply. The railroads saw at once that they were destined speedily to do all the gathering and hastened to secure control of them. Colonel Potts’s first pipe-line purchase was a line running from Pithole to Titusville, which as yet had not been wet.

When the Empire Transportation Company took over this line nothing had been demonstrated but that oil could be driven, by relay pumps, five miles through a two–inch pipe. The Empire’s first effort was to get a longer run by fewer pumps. The agent in charge, C. P. Hatch, believed that oil could be brought the entire ten and one-half miles from Pithole 1026to Titusville by one pump. He met with ridicule, but he insisted on trying it in the new line his company had acquired. The experiment was entirely successful. Improvements followed as rapidly as hands could carry out the suggestions of ingenuity and energy. One of the most important made the first year of the business was connecting wells by pipe directly with the tanks at the pumping stations, thus doing away with the expensive hauling in barrels to the “dump.” A new device for accounting to the producer for his oil was made necessary by this change, and the practice of taking the gauge or measure of the oil in the producer’s tank before and after the run and issuing duplicate “run tickets” was devised by Mr. Hatch. The producers, however, were not all “square”; it sometimes happened that they sold oil by a transfer order on the pipe-line, which they did not have in the line! To prevent these the Empire Transportation Company in 1868 began to issue certificates for credit balances of oil; these soon became the general mediums of trade in oil, and remain so to-day.

One of the cleverest of the pipe-line devices of the Empire Company was its assessment for waste and fire. In running oil through pipes there is more or less lost by leaking and evaporation. In September, 1868, Mr. Hatch announced that thereafter he would deduct two per cent. from oil runs for wastage. The assessment raised almost a riot in the region, meetings were held, the Empire Transportation Company was denounced as a highway robber, and threats of violence were made if the order was enforced. While this excitement was in progress there came a big fire on the line. Now the company’s officials had been studying the question of fire insurance from the start. Fires in the Oil Regions were as regular a feature of the business as explosions used to be on the Mississippi steamboats, and no regular fire insurance company would take the risk. It had been decided that at the first fire there should be announced what was called a “general average assessment,” 1027that is, a fire tax, and to be ready, blanks had been prepared. Now in the thick of the resistance to the wastage assessment came a fire and the line announced that the producers having oil in the line must pay the insurance. The controversy at once waxed hotter than ever, but was finally compromised by the withdrawal in this case of the fire insurance if the producers would consent to the tax for waste. They did consent, and later when fires occurred the general average assessment was applied without serious opposition. Both of these practices prevail to-day. By the end of 1871 the Empire Transportation Company was one of the most efficient and respected business organisations in the oil country.

Its chief rival was the Pennsylvania Transportation Company, an organisation which had its origin in the second pipe-line laid in the Oil Regions. This line was built by Henry Harley, a man who for fully ten years was one of the most brilliant figures in the oil country. Harley was a civil engineer by profession, a graduate of the Troy Polytechnic Institute, and had held a responsible position for some time as an assistant of General Herman Haupt in the Hoosac Tunnel. He became interested in the oil business in 1862, first as a buyer of petroleum, then as an operator in West Virginia. In 1865 he laid a pipe-line from one of the rich oil farms of the creek to the railroad. It was a success, and from this venture Harley and his partner, W. H. Abbott, one of the wealthiest and most active men in the country, developed an important transportation system. In 1868 Jay Gould, who as president of the Erie road was eager to increase his oil freight, bought a controlling interest in the Abbott and Harley lines, and made Harley “General Oil Agent” of the Erie system. Harley now became closely associated with Fisk and Gould, and the three carried on a series of bold and piratical speculations in oil which greatly enraged the oil country. They built a refinery near Jersey City, extended their pipe-line system, and in 1871, 1028when they reorganised under the name of the Pennsylvania Transportation Company, they controlled probably the greatest number of miles of pipe of any company in the region, and then were fighting the Empire bitterly for freight.

There is no part of this rapid development of the business more interesting than the commercial machine the oil men had devised by 1872 for marketing oil. A man with a thousand-barrel well on his hands in 1862 was in a plight. He had got to sell his oil at once for lack of storage room or let it run on the ground, and there was no exchange, no market, no telegraph, not even a post-office within his reach where he could arrange a sale. He had to depend on buyers who came to him. These buyers were the agents of the refineries in different cities, or of the exporters of crude in New York. They went from well to well on horseback, if the roads were not too bad, on foot if they were, and at each place made a special bargain varying with the quantity bought and the difficulty in getting it away, for the buyer was the transporter, and, as a rule, furnished the barrels or boats in which he carried off his oil. It was not long before the speculative character of the oil trade due to the great fluctuations in quantity added a crowd of brokers to the regular buyers who tramped up and down the creek. When the railroads came in the trains became the headquarters for both buyers and sellers. This was the more easily managed as the trains on the creek stopped at almost every oil farm. These trains became, in fact, a sort of travelling oil exchange, and on them a large percentage of all the bargaining of the business was done.

The brokers and buyers first organised and established headquarters in Oil City in 1869, but there was an oil exchange in New York City as early as 1866. Titusville did not have an exchange until 1871. By this time the pipe-lines had begun to issue certificates for the oil they received, and the trading 1029was done to a degree in these. The method was simple, and much more convenient than the old one. The producer ran his oil into a pipe-line, and for it received a certificate showing that the line held so much to his credit; this certificate was transferred when the sale was made and presented when the oil was wanted.

One achievement of which the oil men were particularly proud was increasing the refining capacity of the region. At the start the difficulty of getting the apparatus for a refinery to the creek had been so enormous that the bulk of the crude had been driven to the nearest manufacturing cities—Erie, Pittsburg, Cleveland. Much had gone to the seaboard, too, and Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore were all doing considerable refining. There was always a strong feeling in the Oil Regions that the refining should be done at home. Before the railroads came the most heroic efforts were made again and again to get in the necessary machinery. Brought from Pittsburg by water, as a rule, the apparatus had to be hauled from Oil City, where it had been dumped on the muddy bank of the river—there were no wharfs—over the indescribable roads to the site chosen. It took weeks—months sometimes—to get in the apparatus. The chemicals used in the making of the oil, the barrels in which to store it—all had to be brought from outside. The wonder is that under these conditions anybody tried to refine on the creek. But refineries persisted in coming, and after the railroads came, increased; by 1872 the daily capacity had grown to nearly 10,000 barrels, and there were no more complete or profitable plants in existence than two or three of those on the creek. The only points having larger daily capacity were Cleveland and New York City. Several of the refineries had added barrel works. Acids were made on the ground. Iron works at Oil City and Titusville promised soon to supply the needs of both drillers and refiners. The exultation was 1030great, and the press and people boasted that the day would soon come when they would refine for the world. There in their own narrow valleys should be made everything which petroleum would yield. Cleveland, Pittsburg—the seaboard—must give up refining. The business belonged to the Oil Regions, and the oil men meant to take it.

A significant development in the region was the tendency among many of the oil men to combine different branches of the business. Several large producers conducted shipping agencies for handling their own and other people’s oil. The firm of Pierce and Neyhart was a prominent one carrying on this double business in the sixties and early seventies. J. J. Vandergrift, who has been mentioned already as one of the first men to take hold of the transportation problem, early became interested in production. As soon as the pipe-line was demonstrated to be a success he began building lines. He also added to his interests a large refinery, the Imperial of Oil City. Captain Vandergrift by 1870 produced, transported and refined his own oil as well as transported and refined much of other people’s. It was a common practice for a refinery in the Oil Regions to pipe oil directly to its works by its own line, and in 1872 one refinery in Titusville, the Octave, carried its refined oil a mile or more by pipe to the railroad. Although most of the refineries at this period sold their products to dealers and exporters, the building up of markets by direct contact with new territory was beginning to be a consideration with all large manufacturers. The Octave of Titusville, for instance, chartered a ship in 1872 to load with oil and send in charge of its own agent into South American ports.

The odds against the oil men in developing the business had not been merely physical ones. There had been more than the wilderness to conquer, more than the possibilities of a new product to learn. Over all the early years of their struggle and hardships hovered the dark cloud of the Civil 1031War. They were so cut off from men that they did not hear of the fall of Sumter for four days after it happened, and the news for the time blotted out interest even in flowing wells. Twice at least when Lee invaded Pennsylvania the whole business came to a stand-still, men abandoning the drill, the pump, the refinery to make ready to repel the invader. They were taxed for the war—taxes rising to ten dollars per barrel in 1865—one dollar on crude and twenty cents a gallon on refined (the oil barrel is usually estimated at forty-two gallons). They gave up their quota of men again and again at the call for recruits, and when the end came and a million men were cast on the country, this little corner of Pennsylvania absorbed a larger portion of men probably than any other spot in the United States. The soldier was given the first chance everywhere at work, he was welcomed into oil companies, stock being given him for the value of his war record. There were lieutenants and captains and majors—even generals—scattered all over the field, and the field felt itself honoured, and bragged, as it did of all things, of the number of privates and officers who immediately on disbandment had turned to it for employment.

It was not only the Civil War from which the Oil Regions had suffered; in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War broke the foreign market to pieces and caused great loss to the whole industry. And there had been other troubles. From the first, oil men had to contend with wild fluctuations in the price of oil. In 1859 it was twenty dollars a barrel, and in 1861 it had averaged fifty-two cents. Two years later, in 1863, it averaged $8.15, and in 1867 but $2.40. In all these first twelve years nothing like a steady price could be depended on, for just as the supply seemed to have approached a fixed amount, a “wildcat” well would come in and “knock the bottom out of the market.” Such fluctuations were the natural element of the speculator, and he came early, buying in quantities and 1032holding in storage tanks for higher prices. If enough oil was held, or if the production fell off, up went the price, only to be knocked down by the throwing of great quantities of stocks on the market. The producers themselves often held their oil, though not always to their own profit. A historic case of obstinate holding occurred in 1871 on the “McCray farm,” the most productive field in the region at that time. Prices were hovering around three dollars, and McCray swore he would not sell under five dollars. He bought, hired and built iron tankage until he had upward of 200,000 barrels. There was great loss from leakage and from evaporation and there were taxes, but McCray held on, refusing four dollars, $4.50, and even five dollars. Evil times came in the Oil Regions soon after and with them “dollar oil.” McCray finally was obliged to sell his stocks at about $1.20 per barrel. To develop a business in face of such fluctuations and speculation in the raw product took not only courage—it took a dash of the gambler. It never could have been done, of course, had it not been for the streams of money which flowed unceasingly and apparently from choice into the regions. In 1865 Mr. Wright calculated that the oil country was using a capital of $100,000,000. In 1872 the oil men claimed the capital in operation was $200,000,000. It has been estimated that in the first decade of the industry nearly $350,000,000 was put into it.